The one about the socio-technical model applied to AI.

Much of today’s AI conversation centers on tangible constraints — chip shortages, compute capacity, and the growing energy demands of model training. Those are real limits, and they’ll shape what’s technically possible for years.

But anyone who has lived through an EHR rollout or a “clinical decision support” pilot knows that the harder part often begins after the technology is installed. Once the silicon is humming, we still have to integrate it into the living fabric of care — how clinicians think, how teams coordinate, how patients experience the system.

That’s where the carbon-based agents come in. Not as obstacles, but as the essential medium through which any digital innovation actually becomes care.

The Sittig and Singh (2010) socio-technical model still provides one of the clearest guides here. It lays out eight interdependent dimensions — from technical infrastructure and clinical content to workflow, organizational culture, and external environment. It’s a reminder that safety, quality, and adoption emerge not from the technology itself, but from how these layers interact in practice.

The same logic applies to AI. A model can perform flawlessly in validation but fail to add value at the bedside if it doesn’t align with clinical priorities, decision rhythms, or accountability structures. These systems don’t just plug into existing teams; they subtly reshape how roles are defined, how authority flows, and how judgment is shared.

So yes, the field will need more chips, more power, and more scalable infrastructure. But the real breakthroughs will come from designing AI that supports the people who deliver care and ultimately the carbon-based agents central to their mission: the patient.

would add cost transparency to the complex, opaque medication supply chain believing that this will lead to lower prices and higher value care. Though this may appeal to our intuition, evidence that medication cost transparency leads to higher value care is scant. In order to add to the evidence base, four other investigators and I embarked on a 9-month investigation designing and evaluating the effect of medication cost transparency decision support built into the electronic health record. Bottom line: it makes a difference. The results were recently published and are available on the JAMIA website:

would add cost transparency to the complex, opaque medication supply chain believing that this will lead to lower prices and higher value care. Though this may appeal to our intuition, evidence that medication cost transparency leads to higher value care is scant. In order to add to the evidence base, four other investigators and I embarked on a 9-month investigation designing and evaluating the effect of medication cost transparency decision support built into the electronic health record. Bottom line: it makes a difference. The results were recently published and are available on the JAMIA website:  The

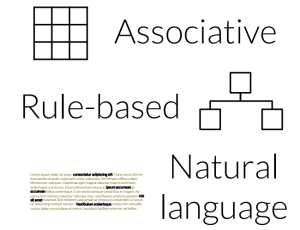

The  Hopkins Informatics Grand Rounds. In it, we talk about some of the history of decision support, the technology behind Symcat, and some additional points about entrepreneurship and web development that excite us.

Hopkins Informatics Grand Rounds. In it, we talk about some of the history of decision support, the technology behind Symcat, and some additional points about entrepreneurship and web development that excite us.

Each year, half a million patients present to emergency departments in the US with acute vestibular syndrome (AVS) characterized by vertigo lasting more than 24 hours. Though this is frequently caused by something benign such as a self-limited viral infection, it may also indicate a more severe condition such as stroke of the posterior circulation. Unfortunately, MRI can miss strokes when obtained early in the disease course meaning half of those with with posterior strokes are inappropriately sent home from the ER.

Each year, half a million patients present to emergency departments in the US with acute vestibular syndrome (AVS) characterized by vertigo lasting more than 24 hours. Though this is frequently caused by something benign such as a self-limited viral infection, it may also indicate a more severe condition such as stroke of the posterior circulation. Unfortunately, MRI can miss strokes when obtained early in the disease course meaning half of those with with posterior strokes are inappropriately sent home from the ER.